Effects of Eligibility Policy Changes

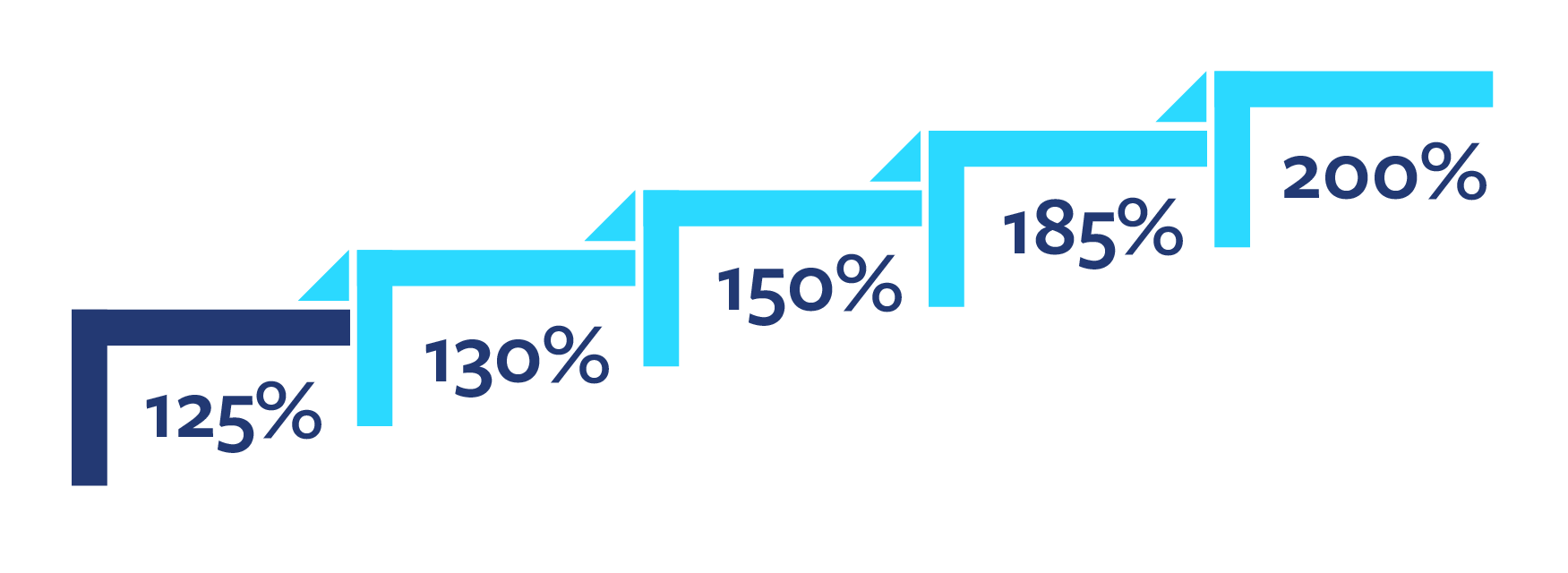

During the period studied (October 2019-September 2024), the income eligibility threshold in Michigan increased four times, moving from 125% of the federal poverty level (FPL) to 200% of the FPL in 2022. Michigan moved from having the lowest eligibility threshold in the country in 2019 to a midway ranking in 2022 (CCDF Policies Database, 2019, 2022). In 2022, a Michigan family of four with an annual household income less than $55,500 (HHS, 2022) who met other criteria could get a CDC Scholarship.

An earlier change, made in 2015, helped facilitate the increases in the cutoff levels. In that shift, Michigan instituted a 12-month eligibility and graduated exit. By lengthening the eligibility period, the paperwork burden was reduced. To take account of families earning more after initial eligibility, the state gradually decreased the assistance as income rose before a family became ineligible, preventing a “benefit cliff.” Suddenly stopping a benefit can undermine a family’s financial improvement (Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, n.d.).

Eligibility Threshold Increase

Overall, eligibility policies resulted in gains in program enrollment, reduced breaks in participation, lowered program exits and greater access to quality care.

The 12-month eligibility and graduated exit policies increased program enrollment and use of the scholarship slightly. They also increased the length of time families were in the program without a break by about 1.5 weeks.

An eligibility threshold increase to 130% of the FPL only showed a slight impact on program participation before a break but did not affect other outcomes.

Other eligibility threshold changes increased program enrollment from 2020 to 2022. The move to 200% of the FPL resulted in an average gain of 600 new families every two weeks in 2022, compared to 400 in 2021.

Families who entered the program in 2021 were more likely to stay with the same provider. However, these eligibility threshold changes did not significantly affect scholarship use, duration of program participation, or access to providers with higher quality levels.

Black families especially benefited from the increase to 200% of the FPL. In 2022, Black families exited the program at a 10% lower rate, in addition to seeing an increase in providers with higher quality levels. They had a higher rate of program exit (31%) in 2020 compared to white families. Similar effects were not seen for other racial/ethnic groups or by geographic region.

Awareness of the eligibility-threshold change was low among the parents interviewed but not providers.

Just 37% of the families interviewed in 2023 were aware of a shift to the latest threshold (200% of the FPL). However, providers were well-informed and able to help connect families they knew with the program.

Grants, Rate Increases, and Other Changes Helped Providers

CDC payment rates for providers changed at multiple points during the years studied. Some increases were temporary, however. In addition to rate increases, Michigan issued relief and stabilization grants to providers. As a result of the pandemic, providers also saw more flexibility in billing rules. For instance, they could bill the state based on child enrollment rather than attendance—a policy which has been maintained.

The provider reimbursement rates in Michigan are set based on provider type (family or group home or center), child age, and provider quality level.

Overall, the payment policies and grants resulted in greater program enrollment, lowered program exits, improved care continuity, better pay for staff at receiving providers, cost savings for families, and provider supply stabilization.

Among the various payment rate increases, the 2017 changes did not have detectable effects on the measures studied. Providers considered the increase too low.

The payment-related changes in 2020 resulted in more stability in program participation. No differences were seen in this outcome by racial/ethnic group.

Families in the first 16 weeks of 2021 were significantly less likely to exit the program and children were more likely to remain with their first provider due to the 30% increase in payment rates.

Over 5,800 licensed providers received at least one stabilization grant from the three rounds.

Providers who had not received a stabilization grant were about three times more likely to close between June 2022 and December 2022 than those who got a grant. The grant-receiving providers were also 10 times more likely to serve families with a CDC scholarship.

Providers reported that families benefited from the grant funding directly (e.g., stable tuition rates) and indirectly (e.g., staffing).

Whether families in subsidized facilities had greater continuity of care could not be determined with certainty from administrative data. Given that those with grants stayed open at higher rates, it is safe to assume that the funding prevented many families from searching for a new provider. The impact of the stabilization grants was short-lived, however, as lump-sum, one-time payments. The grants also did not affect provider supply in the Upper Peninsula, southwest, or southeast regions of the state.

CDC Case Specialization

In this study, through surveys of eligibility specialists, we also examined whether the MDHHS implementation of the Universal Caseload Model (UCL) starting in 2018 had an impact on CDC cases. UCL uses task-based case processing. It allows a pool of eligibility specialists within an office to process shared cases rather than assigning each case to an individual specialist. This approach is intended to improve speed and reliability of service.

Eligibility specialists did not report meaningful differences between the UCL and traditional model.

The survey in 2022 also asked eligibility specialists about the value of CDC program specialization. Some MDHHS offices have specialists who take these cases, as compared to all specialists handling them. CDC specialization can occur in UCL and traditional offices.

Eligibility specialists strongly supported CDC specialization.

In the 2023 survey, 75% of eligibility specialists without a CDC specialist in their office saw value in having one. In addition,CDC-specialized staff were more confident in their ability to process CDC cases compared to those who work in offices without CDC specialization. They also reported better ability to explain CDC policies to families. This potentially could reduce case errors and improve communication with families.